On the poetic lifeworlds of Flash animation

A research project by Johann Yamin

Note: Please use a Flash Player emulator like the Ruffle extension for this page to load correctly.

In Saraswati Gramich’s poetic internet artwork Splash! (2002), worlds of nonhuman companions materialize within the intimate confines of web browser windows. Through hypermedia poetry, she invites visitors to “plunge” into a range of landscapes featuring animated creatures in their home habitats, from ducks quacking as they swim across an illustrated pond to ants scurrying on pebbly terrain. Drawing on SWF Flash animation files, the work is an interactive “technotext” that fulfils N. Katherine Hayles’s delineation of the three characteristics of hypertext: Multiple reading paths, chunked text, and some form of linking mechanism.¹ Given Gramich’s “experiments with form, technology, and poetics,” the work may be seen as a form of “cyborg poetics,” as articulated by Margaret Rhee.²

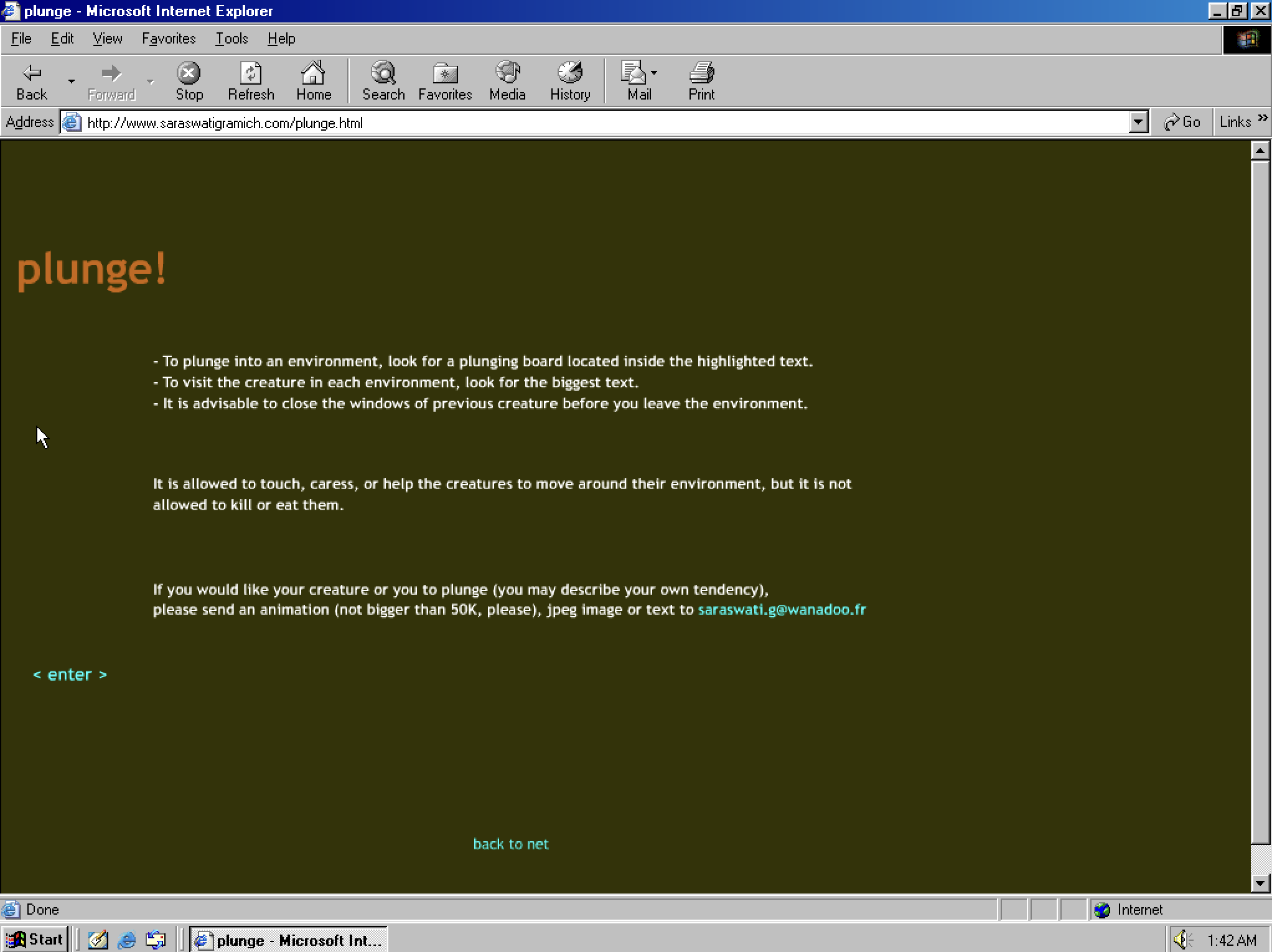

Visitors are first greeted by an instruction page guiding them to find “plunging boards” in the work—clickable linked words or phrases found within the website’s poetic texts. These links open browser popup windows or lead to the next webpage of poetry, offering branching possibilities for encounters with artificial life. Gramich sets up a virtual space that is gentle and nourishing, encouraging visitors through the instructions to “touch, caress, or help the creatures to move around their environment, but it is not allowed to kill or eat them.” Importantly, in Gramich’s write-up in the Rhizome ArtBase, she emphasizes that one of the concerns of the work is about “the fragility of knowledge.”³

Gramich’s Plunge! as a piece of internet art is inherently fragile—prone to link rot, the work is no longer available on the artist’s website. It is made accessible today as a work archived within the Rhizome ArtBase, an archive of over 2,200 internet artworks and other works employing a range of digital forms such as software, code, websites, and games. More significantly, as an artwork relying on SWF Flash animation files, the work is no longer playable without the use of an emulator.

At the end of 2020, Adobe stopped supporting its proprietary Flash Player software, which enabled the delivery of interactive Flash motion graphics over low bandwidths. The ubiquity of Flash on general audiences’ machines and ability to offer interactivity and multimedia works on browsers made the SWF file format one of the most popular multimedia filetypes in internet art. It was the ideal choice for artists seeking to move beyond HTML and Javascript-based internet artworks popular in the late-1990. Without digital preservation efforts, the form of Flash animation would essentially disappear from all present-day web browsers. Through organizations for digital art such as Rhizome and independent developers, Flash animation is sustained through digital preservation efforts and the development of Flash Player emulators.

The fragility of knowledge that Gramich’s work explores gives us various “plunging boards,” to borrow the artist’s term, towards various forms of knowledge that her practice points us to and warrants closer study. This spans the poetics of obsolete technologies such as Flash, the nourishing and collaborative worlds of Southeast Asian feminist art during the 1990s to 2000s (of which Gramich was an active participant), and the cross-cultural nature of Gramich’s practice as an Eurasian artist employing multilingual tactics in her art.

Lifeworlds is a web research project that plunges into these topics by inhabiting the cyborg poetics of obsolete media, drawing upon early vernacular web design and incorporating Flash animation across its pages. It asks: How are we shaped by online and offline worlds that we perceive and experience? What are the technologies and datasets that modulate our perception of these worlds? You are invited to click through the links to explore these questions further.